The Causes of Childhood Scoliosis and Its Progression

Written and reviewed for scientific and factual accuracy by Dr. Austin Jelcick, PhD and Dr. Matthew Janzen, DC. Last reviewed/edited on March 5, 2024. First published January 16, 2018.

If you or your child has been diagnosed with scoliosis, the first and foremost thing to do is educate yourself on the topic to better guide your decision making for treatment. What is scoliosis? How is it defined? What are its signs and symptoms and underlying causes? What is a normal versus abnormal curvature of the spine? What information is accurate and fact checked? All of these questions are important and should be answered before deciding treatment.

The better one’s understanding of a problem, the better their solution to the problem can be.

What is scoliosis of the spine?

Scoliosis can be defined as a combination of the following:

- A lateral bend in the spine. This is evident when viewing the spine from the front or back, called the coronal plane.

- A twist in the spine. The vertebra are twisted out of their normal straight-on alignment. The twist and bend almost always occur together.

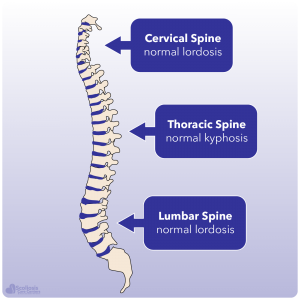

- A loss of normal spinal curves. When viewed from the side, the spine should have three normal curves evident: the cervical lordosis, the , and the lumbar lordosis. Typically in scoliosis there is a loss of thoracic kyphosis.

Does Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Have a Cause?

What is the “force” is that is driving your child’s spine to bend and twist? Getting to the root cause requires a diagnosis that states what is CAUSING the scoliosis. Understanding the CAUSE will help get us closer to a CURE for scoliosis.

Understanding the answer to this can mean the difference in success or failure for treatment. This is a question that must be asked not just by you, but by your managing doctor. Searching for the answer to this question is a key part of our treatment philosophy.

“Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis” Is Not a Complete Diagnosis.

Quite often a child with scoliosis is given the diagnosis of “idiopathic” or “adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.” Let’s break down what this “diagnosis” means:

- Adolescent: A young person who is developing into an adult

- Idiopathic: Too “idiotic” to understand the cause or pathogenesis

- Scoliosis: A three-dimensional torsional deformity of the spine and trunk

Are there types of scoliosis? What’s missing? A statement of the cause of the problem. All too often, this is where the effort to make a diagnosis stops—with the label “idiopathic.” It is important to recognize that this diagnosis fails to specify a root cause, and is merely expressing in Greek that your “adolescent child has scoliosis and we don’t know why.”

When defining any illness or problem, you don’t simply claim that you cannot know the cause; you investigate further to determine and treat the cause rather than only addressing the symptom. Defining scoliosis should be no different: claiming we simply don’t know the cause and moving on is unacceptable. To define scoliosis means that we need to identify not only the signs and symptoms, but also the types and root causes for each type and each patient.

We don’t believe the cause of your child’s scoliosis should remain a mystery.

Some parents, and sometimes even some doctors, behave as though “idiopathic” means there is NO cause. Yet the spine twists and bends for a REASON. Doesn’t the body always have a reason? To define scoliosis as having a completely unknown cause is simply unacceptable.

Treating “adolescent idiopathic scoliosis” as a permanent and final diagnosis denies the rather basic assumption of cause and effect. Perhaps nobody has ever made a diligent effort to find out the reason for your child’s scoliosis. We believe that modern science and caring doctors CAN figure out what’s going wrong, and how to help it. In the words of the French philosopher Voltaire: “No problem can withstand the assault of sustained thinking.”

The 3 Root Causes of Scoliosis

1. Nerve Tension

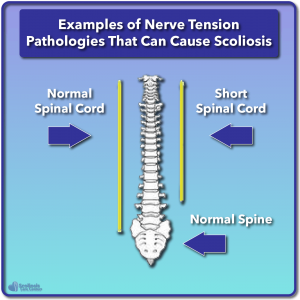

A Nerve Tension scoliosis case is a situation where there is either a tight, inelastic, or tethered spinal cord. The nerve root or meninges create the main driving force causing the spine to coil down into scoliosis. Nerve Tension is likely the most common root cause of scoliosis. If a scoliosis is progressing rapidly, and is diagnosed as “idiopathic,” then chances are it has a Nerve Tension root cause.

Nerve Tension: The Most Common Cause of “Idiopathic” Scoliosis?

The theory that a tight spinal cord could be the cause of adolescent scoliosis was first proposed by a neuroradiologist named Dr. Roth in 1968. The theory was further expounded upon by Dr. Porter in 2001, and has become known as the Roth-Porter Hypothesis.

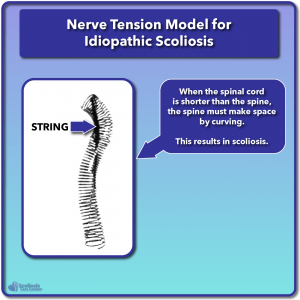

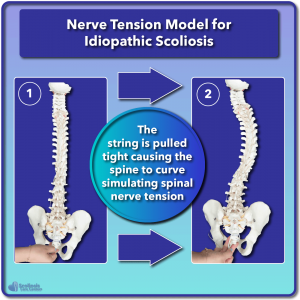

To understand how a tight spinal cord can cause scoliosis, Roth & Porter used the analogy of a string that runs through the middle of a spring. The spring represents the spinal bones, and the string represents the spinal cord. As the string is pulled tight, the spring coils down into a scoliotic shape.

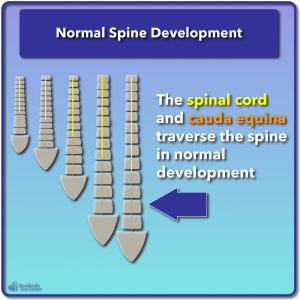

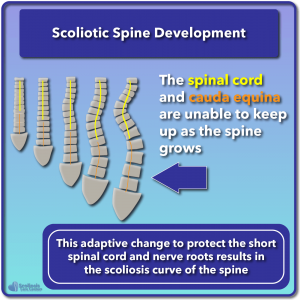

Most commonly, nerve tension will be due to a problem called Uncoupled Neuro-Osseous Development, which means that the bones are growing faster than the nerves, creating a spinal cord or meningeal tension. This relatively short spinal cord results in a tugging force on the posterior parts of the vertebral column, causing the column to compress down.

Just like tension on a string will cause the spring to coil down, so tension on the spinal cord will cause the spine to coil down. This coiled-down scoliotic position actually relieves the tension on a tight spinal cord. Thus we can define scoliosis as an adaptive position in response to nerve tension.

Examples of Nerve Tension pathologies that can cause scoliosis include:

- Tumors or cysts: These can bind the meninges or cord and cause a tension on the nerves, leading to scoliosis. They also may create neuro-muscular dysfunction as described in root cause number 3.

- Intraspinal anomalies: The spinal cord or nerves develop embryologically in a way such that one side or one part of the cord is pulled tight at birth. Even though the problem happens at birth, it may not appear until the child begins to have growth spurts.

- Tethered Cord Syndrome: This is again a condition from birth that causes the entire spinal cord to be pulled noticeably lower towards the sacrum, placing tension on the spinal cord.

- Uncoupled Neuro-Osseous Development: This means that the spinal cord (neuro) is not growing as fast or as long as the bones of the spine (osseous). THIS is likely to become recognized as the MOST COMMON CAUSE of adolescent scoliosis.

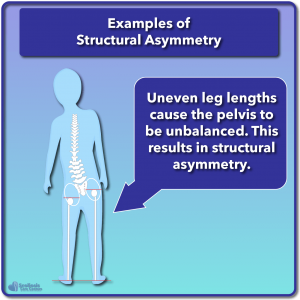

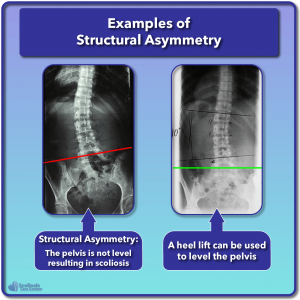

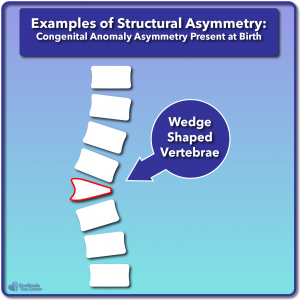

2. Structural Asymmetry

“Structural” root causes may refer to bones that are asymmetric or incorrectly shaped. For example, a half-formed vertebra at birth, known as a hemi-vertebra, may also create scoliosis. Another example of structural-biomechanical scoliosis is when one leg grows a little longer than the other, causing the sacrum to be un-level. The sacrum is the base of the spine, so when the sacrum tilts, the spine tilts, and there can be a mild (and sometimes moderate) scoliosis as a result.

“Structural causes” may also apply to ligament damage from trauma or from degeneration of discs. If key stabilizing ligaments of the spine are damaged or torn, the vertebra may tilt in response, creating a scoliotic curve. Therefore in these situations we can define scoliosis as having an underlying structural cause.

These conditions are very common and USUALLY only cause mild to moderate non-progressive scoliosis.

3. Neuro-Muscular Pathology That Causes Scoliosis

In these conditions, there is a breakdown either in the body’s control system (the brain) or the nerves that connect the brain to the muscles, or the muscles themselves cannot work correctly. Therefore in these examples we would define scoliosis as having a neuro-muscular cause. For example, in cerebral palsy, there is a lack of proper central nervous system control within the brain. In poliomyelitis, the peripheral nerves that carry signals from the brain to the muscles are damaged. In muscular dystrophy, there is weakness of the muscles, rendering the muscles unable to support a straight spine. Neuro-muscular pathology cases tend to be more aggressive. Progression of the scoliosis—the tendency for the curve to grow large—is often quite high.

Scoliosis Rapidly Worsens with Growth

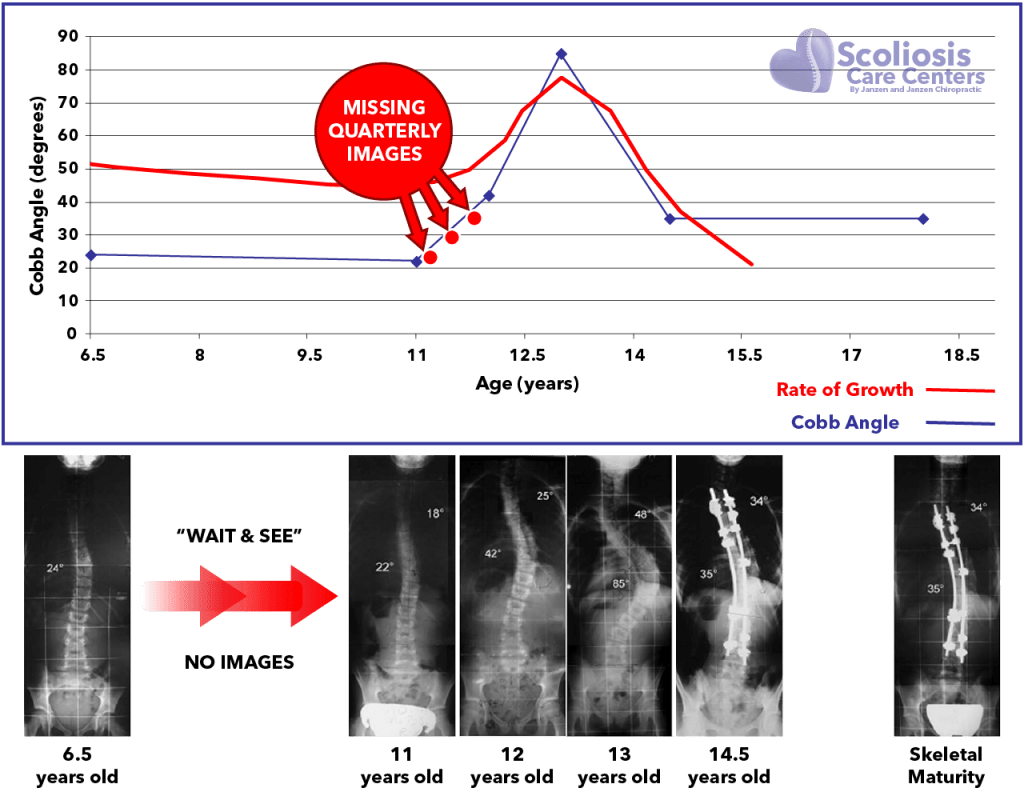

This may be the single most critical thing that you need to understand about childhood scoliosis: It rapidly worsens with the child’s growth spurts.1,2 In fact, the faster the child grows the faster scoliosis can worsen. This means that scoliosis does not get worse at a steady, linear rate. Rather, scoliosis can rapidly increase in size within a matter of a few months.

This phenomenon often leads to the belief in parents that their child’s scoliosis just “popped up” overnight. “In the spring my child was screened for scoliosis and was fine, and this summer she has a 40 degree curve”. In truth, the curves will often develop long before it is visibly noticeable; but with sudden growth spurts the curve grows rapidly worse, which results in a curve that is obvious and easily seen. Therefore we can define scoliosis (idiopathic scoliosis) as not just affected by growth, but the RATE of growth (which can also be utilized as a tool; you can learn more here).

Scoliosis Progression is Rate of Growth Dependent:

The faster the child grows, the faster scoliosis can worsen!

What is also important to understand about this “growth storm” is that watching a scoliosis curve every 6 months to a year with an X-ray may be too long of an interval. Significant worsening of the curve can take place during just a couple months of a growth spurt and therefore, we strongly recommend taking an image of the spine every 3 months or sooner if a child is suddenly shooting up in height.

If scoliosis changes rapidly with growth spurts, why don’t most doctors image the spine more frequently or when a patient grows? The reasons likely are:

- Harmful X-ray radiation must be used to see the spine, so it is important to limit radiation exposure. Repeated X-rays have unfortunately been linked to cancers in scoliosis patients.3,4 For that reason, one must be cautious with both the frequency of exposure and the area of the body exposed to an X-ray. Whenever possible, doctors should use lead to protect the breast, lungs, thyroid, and gonads when taking an X-ray.

- Many doctors believe that they can’t do anything to stop the escalation of scoliosis unless it has reached “surgical range” of 40 or 50 degrees in which case, a full spine fusion can be recommended.

Knowing that scoliosis can worsen so rapidly with growth, what can you do to prevent this from happening? Here is what we recommend:

- Obtain quarterly imaging using standing Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Radiation-free standing MRIs can replace X-rays for evaluating the progression of a curve. MRI is harmless compared to X-rays, which are damaging. Most MRI’s are designed to be performed lying down; however, the standing position is the gold-standard for measuring scoliosis. This is because being out of gravity while laying down masks the severity of the curve in a less than predictable amount.5 Standing MRI provides a reliable, safe way to image scoliosis progression as often as is needed.6 Standing Scoliosis MRIs can be scheduled by calling our center.

- Take corrective action immediately. If your case is that of a child who is growing, it is critical for them to be in a highly corrective brace as soon as possible. Scoliosis bracing utilizing a well-made brace that is worn full time has been shown to greatly reduce the risk of scoliosis progression. Conversely, time spent without a brace during the growth period has been shown to result in 58% of high-risk cases worsening beyond 50 degrees and resulting in surgery.7

- Monitor the rate of growth. Measuring growth monthly and watching for the growth “spurts” – or the high rates of growth – will give a good indication of when a child is most at risk for getting worse. Notify your doctor if there has been a growth spurt!

Progression of Scoliosis

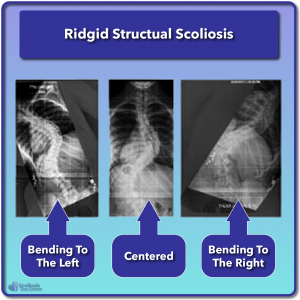

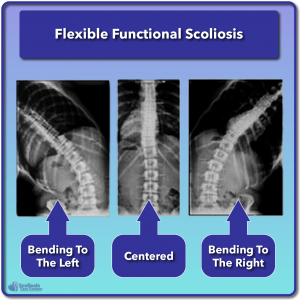

Whatever the root cause, however we define scoliosis based on a patient’s symptoms, it will usually begin as a small, flexible scoliosis. At this stage, the spine is still capable of going through its normal range of motion (more or less). In a small, flexible, or “functional” scoliosis, lateral bending X-rays would show an easy correction of the curve when bending the spine sideways to the left and right. As a curve grows, increasing distortion occurs in the soft tissues of the spine, which leads to loss of normal range of motion. When normal range of motion is lost, severe stiffness can set in.

Structural Scoliosis Defined vs. Functional Scoliosis Defined

Structural scoliosis is a term applied when the curve has become stiff, inflexible, and rigid. Calling scoliosis “structural” does NOT mean the curve was caused by a structural asymmetry, such as a wedge-shaped vertebra. It would be more accurate to simply call the scoliosis “rigid” instead of “structural.”

Some doctors seem to prefer the use of the word “structural” in order to divide scoliosis into two categories: (1) Functional scoliosis (flexible); (2) Structural scoliosis (rigid).

This may be considered a false dichotomy, as most curves have BOTH some functional and some structural qualities. Also, using the term “structural” for a curve that is rigid creates the false impression that the curve is being caused by bones that are “structurally” misshaped. In truth, most larger, rigid curves have relatively minimal distortion in the bones. Finally, the term “structural” is often used to communicate to the patient that nothing at this point could straighten the spine, except surgery. This is not the case.

As curve size increases, the ability to exercise the spine throughout its full range of motion is lost. This results in the scoliosis becoming rigid and stiff primarily due to changes in soft tissue. Secondary stiffness comes from small changes in the shapes of the bones.

How a Small Flexible Curve Becomes a Large Inflexible Curve

In child and adolescent scoliosis, a small flexible curve can quickly become a large, stiff, and rigid.

What is happening?

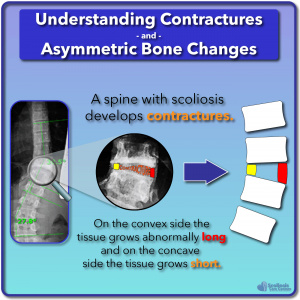

First, during growth of the spinal bones, the tightness of the spinal cord causes the vertebra to “coil down” like a spring that has a tight string run through it. The spine is now constantly postured in a scoliotic pattern, unable to straighten even when the patient tries to bend out of it. This means that the ligaments, muscles, and discs are no longer being exercised through their normal range of motion. Failure to move muscles and joints always results in stiff “contractures” of the joints.

These “contractured” joints are so stiff, that it will FEEL like bone running into bone, when in reality, it is really just soft tissue that has become stiff, shortened, and tough. This is good and bad news. Good news because soft tissue contractures can be loosened up with proper mobilization. Bad news, because it is a difficult and arduous process to loosen up contractured soft tissue around the joints.

The longer the contracture is present, the tougher it is to treat. This is why non-surgical scoliosis curve reduction is most effective while the spine is still growing.

Events Occurring During Scoliosis Progression

- Early stage flexible, functional scoliosis

- Progression of curve size

- Loss of range of motion leads to joint contractures of spine

- Stiffer, rigid, “structural” scoliosis

- BONY change—the BONES DO finally change shape in response to the stress placed on them.

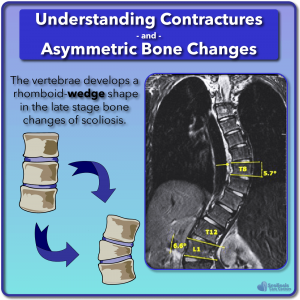

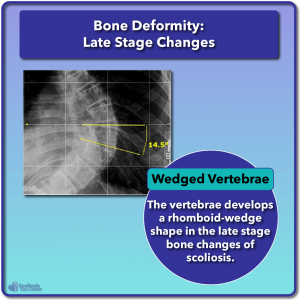

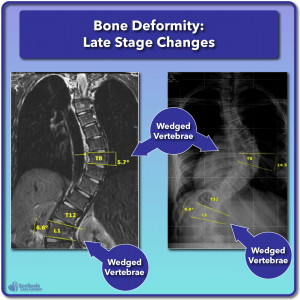

That last point—number 5—is the worst part of the progression of scoliosis. The bones do finally change shape in response to the stress of the scoliosis, causing wedge-shaped vertebra, asymmetric pedicles, and rib cage deformity.

Bone Deformity In Scoliosis

In the early development of scoliosis, most of the distortion that allows scoliosis is primarily in the soft tissue. Eventually, some of that distortion leads to changes in the shape of the rib cage. Vertebra become slightly wedge-shaped and asymmetric.

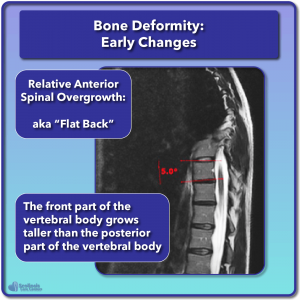

Early Stage Bone Changes

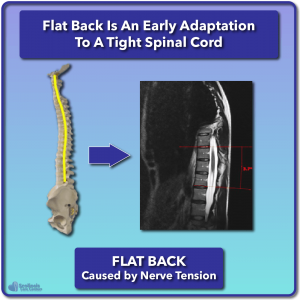

Early stage bone changes in small scoliosis are observed. Those changes are most noticeable in the front part of the thoracic vertebral bodies. It is evident that the front part of the vertebral body can grow taller than what is normal. This is called Relative Anterior Spinal Overgrowth. The word “anterior” simply means “front”—that the front of the vertebra is growing taller than it should. This can lead to a “flat back”—a loss of the normal thoracic kyphosis.

Relative anterior spinal overgrowth and a loss of the normal thoracic spinal curve is most likely in response to nerve tension. Nerve tension will cause the thoracic spine to flatten out its normally curved shape. The loss of thoracic curve, or “flat back,” is a position that relieves tension on the spinal cord. The “flat back” is an early adaptive position in response to a tight spinal cord. It is suspected that nerve tension occurs first, followed by the flat back in response to the nerve tension.

Late Stage Bone Changes

Three bone changes take place as a scoliosis curve becomes larger:

- The rib cage distorts to adapt to the growing scoliosis.

- The pedicles of the spine may grow asymmetric in length and thickness.

- The normally rectangular vertebra may develop a slight rhomboid-wedge shape at the apex of curves.

Bone deformity is NOT most commonly what limits a spinal surgeon when straightening a spine. It is nerve tension from a tight spinal cord.

Detecting the Risk of Scoliosis

So what are the risk factors for scoliosis? When should one start looking for early signs and other associated risk factors? What are your scoliosis treatment options? Treating a curve before it progresses beyond 25 degrees is met with a 100% success rate at Scoliosis Care CentersTM. Now it is possible to catch the warning signs of scoliosis before a curve even begins. Learn about the Cox Test here and how it may help you detect and even potentially prevent scoliosis and scoliosis surgery in a growing child.

References

- Dimeglio A, Canavese F. Progression or not progression? How to deal with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis during puberty. J Child Orthop 2013;7:43–9.

- Ylikoski M. Growth and progression of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in girls. J Pediatr Orthop B 2005;14:320–4.

- Hoffman DA, Lonstein JE, Morin MM, Visscher W, Harris BS, Boice JD. Breast cancer in women with scoliosis exposed to multiple diagnostic x rays. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989;81:1307–12.

- Simony A, Hansen EJ, Christensen SB, Carreon LY, Andersen MO. Incidence of cancer in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients treated 25 years previously. Eur Spine J 2016;25:3366–70.

- van Loon, Piet J M, Kuhbauch BAG, Thunnissen FB. Forced lordosis on the thoracolumbar junction can correct coronal plane deformity in adolescents with double major curve pattern idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:797–801.

- Auerbach JD, Lonner BS, Dean LE, Goldstein Y. The Feasibility of Radiation‐Free Diagnostic Monitoring in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis using a Novel, Upright Positional MRI Protocol, E‐Poster #31. Spine Journal Meeting Abstracts 2009;10.

- Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Wright JG, Dobbs MB. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1512–21.