Written and reviewed for scientific and factual accuracy by Dr. Austin Jelcick, PhD and Dr. Matthew Janzen, DC

Causes of Scoliosis

One question frequently asked by patients and their families after being diagnosed is how scoliosis is caused. Scoliosis is a type of spinal deformity that occurs in three dimensions. Instead of simply being a curve in two dimensions, there often is rotation, making scoliosis a three dimensional problem. In addition to being a 3D issue, there are different types of scoliosis which need to be treated differently. Some types only involve the spine and its muscles and connective tissues (ie. joints, ligaments and tendons) while others are what is known as “syndromic” meaning they are part of a larger syndrome of other symptoms and health problems. Additionally, other types of scoliosis include congenital scoliosis, neuro-muscular scoliosis (which often times is part of a syndrome, or syndromic), and last but not least, idiopathic scoliosis.

Now, you may have heard the term “idiopathic” or “idiopathic scoliosis” before. While the term “idiopathic” means that something “arises suddenly” or has an “unknown cause”; idiopathic scoliosis can be better thought of a case of scoliosis which does not fall under the other categories (ie. syndromic). This also highlights a myth: that adolescent idiopathic scoliosis has no cause.

This myth exists due to the doctors commonly calling a case of scoliosis “idiopathic” simply because they do not know the cause of a given case of scoliosis; often times because it is not immediately obvious. This is not to say that the scoliosis truly has some mystical unknown cause, but rather that the cause simply has not been identified YET. Here is an example: If you were to wake up with a sore neck, you could call your neck pain “idiopathic” because you don’t know what caused it. However, the real cause is not truly a mystery as you could have slept on it wrong, pulled a muscle, etc.; you simply have not figured out the cause YET.

The use (and over use) of the label “idiopathic” has somehow lulled the minds of doctors and clinicians into thinking that it is not possible to know what is causing scoliosis in most idiopathic cases. Unfortunately, sometimes parents and patients can misinterpret this to mean that “there is no cause” and that their case of scoliosis is caused by an absolute mystery; after all if the doctor says the case is idiopathic and the cause is unknown, who are we to question it?

The truth is, we can have a high level of certainty regarding how a scoliosis is caused; why the curve may be getting worse (progressing), and even what we might be able to do to address and control that “mysterious” cause.

Scoliosis Types

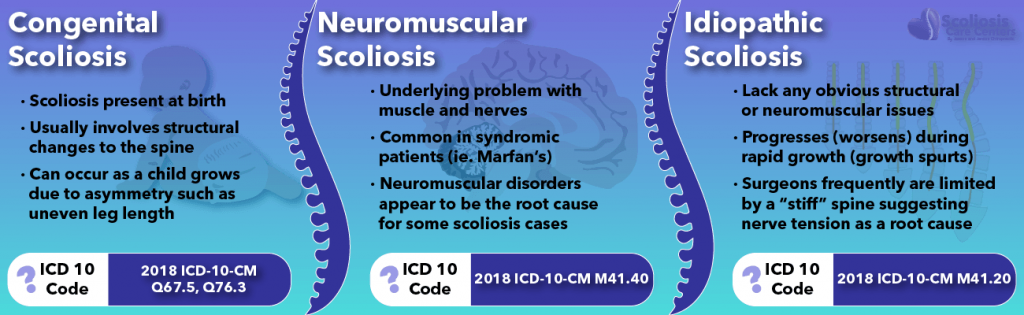

Based on current medical and scientific research, scoliosis can be categorized into three major types; each with their own causes. For each type you can find the associated ICD 10 code as well. The ICD 10 codes which have been provided are scoliosis unspecified ICD 10 codes rather than specific (ie. thoracic) codes.

Congenital Scoliosis

ICD 10 Code: 2018 ICD-10-CM Q67.5, Q76.3

Congenital scoliosis is a type of scoliosis that a child is born with. Typically with congenital patients, a morphological change (a physical, structural change) is present such as a structurally wedged vertebra, or an asymmetric vertebra. While not all congenital scoliosis cases have vertebra asymmetry, this is a very commonly understood reason why a child would be born with a scoliosis. The take-home lesson here is that the structural change (the asymmetry) may be how a congenital scoliosis is caused.

Structural asymmetry does not merely happen in the womb during a child’s development. These structural changes can also happen as a child develops and grows during childhood in an uneven or asymmetric way. One common developmental (happens with growth) asymmetry is when a child has one leg shorter than the other; also known as an anatomic short leg. In this case one leg grows faster than the other, leading to an uneven pelvis. The pelvis is no longer even or level, and as a result the spine becomes unlevel as well.

For the sake of simplicity and categorizing scoliosis types by what ultimately causes them, we would propose that instead of “Congenital” Scoliosis, referring to it as a “Structural Asymmetry Scoliosis” would be better. By doing this we more clearly state that a structural asymmetry is at the root cause of the problem.

Neuromuscular Scoliosis

ICD 10 Code: 2018 ICD-10-CM M41.40

Neuromuscular scoliosis is a type of scoliosis where a known neuromuscular problem ( a problem with the muscles and nerves) prevents the body from being able to hold the spine in an aligned position as the patient grows. This type of problem can be due to an issue somewhere in the muscles, in the nerves to the muscles, or somewhere in the brain as it orchestrates neuromuscular control. As we discussed earlier, neuromuscular scoliosis commonly occurs in individuals with other syndromes and can sometimes be thought of as “syndromic scoliosis” despite its neuromuscular nature. Some common conditions in this category are cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, or poliomyelitis. The list of genetic syndromes and diseases known to cause or be associated with scoliosis is a long one, which grows each year as new research is conducted and pours in. One thing is agreed upon by all experts is that neuromuscular disorders, such as cerebral palsy, appear to be the root CAUSE of some cases of scoliosis.

Idiopathic Scoliosis

ICD 10 Code: 2018 ICD-10-CM M41.20

Idiopathic scoliosis is the classical “we don’t know” category:; the cause remains yet undiagnosed and so it is simply called idiopathic. Because of this, cases of idiopathic scoliosis can potentially represent a wide variety of underlying causes, possibly even including causes from the previously discussed categories (congenital and neuromuscular), simply because the underlying cause has not been properly diagnosed.

All sorts of varieties of scoliosis can end up in the idiopathic category when they are not yet diagnosed. In a perfect world, every patient that initially says “I don’t know the cause” would eventually be properly diagnosed and know how their scoliosis is caused. Unfortunately, most do not and their case is eternally referred to as idiopathic.

What is interesting about MOST cases of scoliosis that end up remaining in the idiopathic category, is that they clearly lack any obvious neuromuscular or structural asymmetry at their root. However, there is one more clue as to what causes most “idiopathic “ cases: The condition known as “tethered cord syndrome”.

Scoliosis Causes: Tethered Cord Syndrome

ICD 10 code: 2019 ICD-10-CM Q06.8

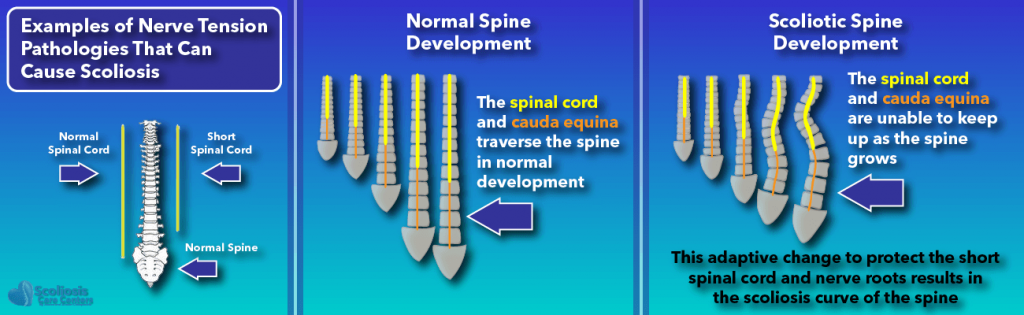

Tethered cord syndrome is a condition that occurs when the spinal cord becomes abnormally stuck to the bottom of the spinal canal during embryological development. So what happens as a result? Well, at birth the spinal cord is stuck, but in most cases no scoliosis occurs UNTIL the patient begins to grow. As the patient grows during their childhood, their spinal cord (which is stuck) begins to pull on the spine (because it is stuck or “tethered”) which causes the spine to coil down, causing a scoliosis that worsens with growth (you can learn more about scoliosis worsening due to growth here).

This is a wonderful explanation about why patients with tethered cord syndrome can get scoliosis and how it causes it, but how does this relate to idiopathic cases? Well, the lesson we can learn from tethered cord syndrome is this: Tension along the spinal canal or neuraxis can lead to scoliosis. This may sound like a new and radical idea, however you’ll be surprised to know this concept has been around for over 50 years!

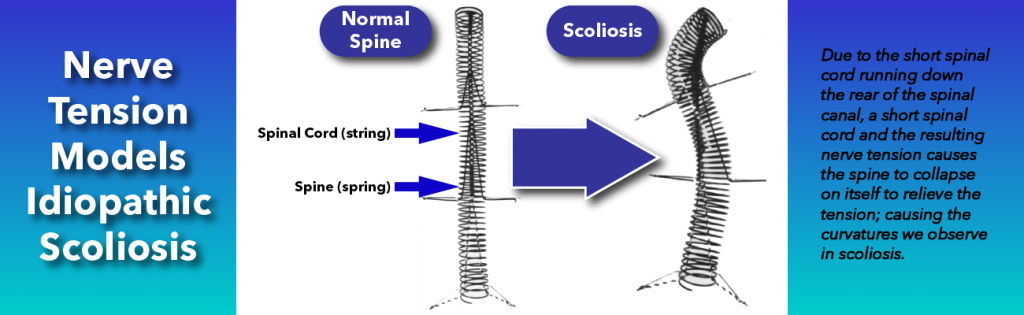

How Scoliosis is Caused by Nerve Tension

Back in 1968, Dr. Milan Roth proposed that spinal cord tension, or a short spinal cord could be at the root cause of most idiopathic scoliosis, even if there was no obvious tethered cord syndrome. According to Dr. Roth’s research, the spinal cord and nerve roots may grow at a slower rate than the bones of the spine. Because the nervous system’s development is more complicated than the development of the spinal bones, it is more vulnerable to having issues. If the spinal cord and nerve roots lag behind, the spine grows faster than the nerves, the spine becomes longer, and thus needs to adapt to the shorter spinal cord.

Simply put, the bones of the spine are growing faster than the nerves can, which causes increased tension in the spinal cord, which then pulls down on the spine, ultimately causing scoliosis. What is interesting to note, is that during spinal fusion surgeries surgeons are often limited by a “stiff” spinal cord which restricts how straight they can make a spine during surgery. It is for exactly this reason why surgeons will monitor the spinal cord and nerves to make sure they don’t “over correct” the spine, accidentally causing paralysis.

This hypothesis on nerve tension has been growing in popularity. In fact, the nerve tension hypothesis has been placed as a possible central cause by some of the leading researchers in scoliosis causation. One such example is Dr. Burwell in his 2016 paper titled “Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS): a multifactorial cascade concept for pathogenesis and embryonic origin.”

In this scientific publication, Dr. Burwell also notes that other researchers have observed the spine growing faster than the spinal cord, supporting Dr. Roth’s studies. In the example cited, Dr. Chu et al. found that while the spinal cord was of normal length, the spine grew more than normal (overgrowth) which creates a tension or tethering effect, causing and also causing progression (worsening) of thoracic adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. The cause of this unequal growth of the spine and spinal cord is still being studied and likely has many contributing factors (multifactorial).

Scoliosis for Dummies: Closing Comments

While all cases of scoliosis are similar in some ways: a three dimensional deformity, lateral curve in the spine, etc. no two cases are the same and there are distinct types of scoliosis. Just as there are scoliosis types, how scoliosis is caused varies depending on the underlying cause and type. Scoliosis can be part of a syndrome while also being of a neuromuscular nature. Similarly, scoliosis can occur very early in childhood and be congenital due to structural abnormalities in the spine. Lastly, scoliosis can appear to have an unknown cause and be dubbed “idiopathic”, when in fact there IS a knowable underlying cause; the cause simply being undiagnosed.

We know that for over 50 years, scientists have thought that a tension in the nerves due to an unequal growth of the spine versus the nerves can be an underlying root cause of idiopathic scoliosis. This unequal growth, also known as uncoupled neuroosseous development creates tension along the spine, causing it to coil down into a scoliotic shape. Recent scientific studies have suggested many things are involved in this uncoupled development.

It does not matter what type of scoliosis a patient has. Whether it be congenital, neuromuscular, syndromic, or idiopathic, every case of scoliosis DOES have an underlying cause just WAITING to be discovered and diagnosed. With improved screening methods designed to look not only for scoliosis, but also for underlying nerve tension; and with radiation-free methods (MRI) to visualize the spine and help detect other underlying issues, the term “idiopathic” will hopefully be a thing of the past sooner rather than later. If we understand the cause, we can effectively treat it rather than the symptom, increasing quality of care. Additionally, if we know the cause, we can intervene earlier, potentially preventing a problem before it has time to occur.

After all, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” –Ben Franklin.

References

- Burwell, R. Geoffrey; Clark, Emma M.; Dangerfield, Peter H.; Moulton, Alan (2016): Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS): a multifactorial cascade concept for pathogenesis and embryonic origin. In Scoliosis and spinal disorders 11, p. 8. DOI: 10.1186/s13013-016-0063-1.

- Chu, Winnie Cw; Lam, Wynnie Mw; Ng, Bobby Kw; Tze-Ping, Lam; Lee, Kwong-Man; Guo, Xia et al. (2008): Relative shortening and functional tethering of spinal cord in adolescent scoliosis – Result of asynchronous neuro-osseous growth, summary of an electronic focus group debate of the IBSE. In Scoliosis 3, p. 8. DOI: 10.1186/1748-7161-3-8.

- Roth, M. (1968): Idiopathic scoliosis caused by a short spinal cord. In Acta radiologica: diagnosis 7 (3), pp. 257–271.

- Roth, M. (1981): Idiopathic scoliosis from the point of view of the neuroradiologist. In Neuroradiology 21 (3), pp. 133–138.

- van Loon, P. J. M.; van Rhijn, L. W. (2008): The central cord-nervous roots complex and the formation and deformation of the spine; the scientific work on systematic body growth by Milan Roth of Brno (1926-2006). In Studies in health technology and informatics 140, pp. 170–186.